By: Keegan O’Brien*—

The Stonewall Riots gave birth to the modern LGBTQ movement, as we know it. On its 51st anniversary, we are witnessing the most significant rebellion against racism and police violence in more than half a century.

Today’s uprising is unfolding in a context where public policy and mainstream opinion is shifting decisively in favor of LGBTQ equality. We see this in the legalization of gay marriage, the inclusion of sexual orientation and gender identity in workplace non-discrimination laws, and increased trans and queer visibility and representation in popular culture, among other places.

On the other hand, the Trump administration has spent its first term in office inciting racist bigotry and fueling its right-wing base. Above all, it has provoked attacks against LGBTQ communities that threaten to turn back the clock and undermine the gains won through decades of struggle.

Given this contradictory landscape, it is necessary to evaluate the state of LGBTQ life and politics under Trump, to analyze the significance of the ongoing anti-racist rebellion and its implications for the trans and queer movement, and to excavate the radical legacy of the Stonewall Rebellion and the Gay Liberation Movement. In doing so, I will recover the lessons it holds for the struggle for trans and queer liberation today, considering the intersection of this struggle with the fight for Black lives.

The State of LGBTQ Life Today

From attacks against trans people to the defense of “religious liberties,” the Trump administration has made it a point to target the most oppressed and vulnerable in our society. Some of the Trump Administration’s most egregious attacks on LGBTQ people include:

- In the summer of 2017, in a series of classic Trump tweets, the president announced that he would be reinstating the military’s ban on transgender people serving in the military, spuriously claiming that the military could not afford the high rate of health care costs.

- In the same year, Education Secretary Betsy DeVos rescinded Obama-era guidelines requiring that schools provide basic civil rights protections to transgender students. In the context of a school system where trans students are regularly bullied and harassed and already experience disproportionally higher levels of depression and suicide, this decision will have highly injurious consequences.

- Trump has continued to stack the federal court system with judicial nominees who are openly and vehemently opposed to LGBTQ rights.

- The Justice Department rescinded an Obama-era federal memo declaring trans people to be protected under civil rights laws and has come out in support of anti-trans “bathroom bill” legislation. The bigoted right has taken this as a green light to go on the offensive, using the guise of “religious liberties” and “bathroom bills” to chip away at established civil rights protections across the country at the local, state, and federal levels.

- The administration has provided a set of “religious liberties” guidelines to federal agencies asking them to respect “religious liberty protections” in all levels of the federal government. The Department of Health and Human Services also created a new agency, the Division of Consciousness and Religious Freedom, to ensure that the “religious liberties” of providers are not violated.

- Without any explanation, the administration fired the entire Presidential Advisory Council on HIV/AIDS in December and refuses to recognize LGBTQ Pride Month in June.

- It allowed emergency shelters to deny housing to transgender and gender non-conforming people. Despite the fact that LGBTQ people are significantly more likely to experience homelessness in their lives, HUD Secretary Ben Carson has proposed a rule to permit emergency shelters to deny access to, or otherwise discriminate against, transgender and gender non-conforming people who lack homes.

- It supported employment discrimination against LGBTQ people by submitting amicus briefs to the U.S. Supreme Court advocating against LGBTQ people’s inclusion in workplace non-discrimination policies and publicly coming out against the Equality Act.

- It instituted changes to the Affordable Care Act (ACA) by removing explicit protections for LGBTQ people in healthcare programs. It did so by excluding LGBTQ people from protections from discrimination based on sex stereotyping and gender identity. In a healthcare system already marked by transphobia and homophobia, this will disproportionately impact working-class and poor trans and queer people, particularly those of color.

Race, Class, and LGBTQ oppression

Compounded with broader attacks against working-class and oppressed people, the situation for the most vulnerable trans and queer folks remains extremely precarious. It is now approaching a state of crisis.

Nothing demonstrates this more starkly than the level of violence endured by trans women of color. In 2017, 28 transgender people, overwhelming trans women of color, were killed as a result of hate-motivated attacks. Trans women of color make up 67 percent of homicides against the LGBTQ community and Black trans women have a life expectancy rate of 35 years. The compounding effects of poverty, violence, and bigotry are quite literally stealing away the lives of trans women of color.

The stories of Selena Reyes-Hernandez and Dominique Rem’mie Fells, two trans women of color brutally murdered earlier this summer, are only the most recent examples. Selena grew up in the Chicago area. After disclosing that she was transgender to an intimate partner, Selena was shot in the head by Orlando Perez, an 18-year-old high school student. After murdering Selena, Perez returned and continued to shoot her numerous times. Selena’s family refused to recognize their trans daughter, burying her under her dead name. Even in death, transphobia continues.

Rem’mie Fells, a young woman from Philadelphia, was described by friends as a bright and loving soul, a passionate dancer and artist who had dreams of going back to school for fashion. She was brutally murdered, her body found dismembered and bludgeoned to death. As her friend Kendall Stephens explained in an interview, “We live with a constant fear of being assaulted and being murdered before our time. It seems to be a trans person of color, that’s like a death sentence.”

As a report detailing the simultaneous layers of structural oppression and their effects explains,

While the details of these cases differ, it is clear that fatal violence disproportionately affects transgender women of color, and that the intersections of racism, sexism, homophobia, and transphobia conspire to deprive them of employment, housing, health care, and other necessities, barriers that make them vulnerable.

The picture for young queer people, especially trans youth, is equally disturbing. Although schools should be a safe place for students from the oppression and discrimination of society, too often they are not.

In a recent study, 82 percent of trans youth reported feeling unsafe at school, 44 percent experienced physical abuse, and 67 percent were bullied by their peers. The emotional and psychological toll social and family rejection can take on LGBTQ youth can be traumatizing and have dangerous physical consequences.

Lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth contemplate suicide at almost three times the rate of their straight peers, and more than 40 percent of transgender adults report having attempted suicide.

Of the more than 1.7 million homeless youth in the U.S., 40 percent identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer, and almost all report rejection from family, community, and/or peers as the primary reason for being forced onto the streets.

In an era of mass incarceration, it is no surprise that a criminal justice system designed to target low-income Black, Latinx, and immigrant communities and working-class people, disproportionately affects those same populations in the LGBTQ community.

With the advent of “quality of life” laws in the 1990s, many cities saw an increase in arrests for panhandling, loitering, and other petty crimes. This was part of a larger effort to “get tough” and “crackdown” on crimes that politicians and law enforcement argued worsened the “quality of life” and led to more severe forms of criminal behavior. Rather than making communities safer, these get-tough measures criminalize the symptoms of capitalist exploitation and oppression and result in more people being swept into the criminal legal system for nonviolent offenses and petty infractions.

Poor and homeless LGBTQ youth, particularly trans women of color, who are pushed into the informal economy for survival are most frequently targeted by “broken windows” policing and are disproportionately brutalized by police, penalized, and incarcerated as a result. Once swept into the system, already marked by multiple racialized, gendered, and classed narratives of social deviance and abnormality, they face high levels of racist, homophobic, and transphobic discrimination and bias at the hands of police, lawyers, probation officers, and judges.

Nothing demonstrates this more clearly than the story of Layleen Polanco. Layleen was a 27-year-old Afro-Latinx trans woman that died at Riker’s Island. After she had an epileptic seizure, the staff mocked and derided her and refused to provide medical care that could have saved her life. Layleen was initially arrested for a misdemeanor assault charge, after which she was held on prior drug and sex work charges. Unable to afford her $500 bail, Layleen was detained in solitary confinement where she was kept for 17 hours a day.

Layleen’s story illustrates the barbarity of the criminal legal system and the ways racism, trans-misogyny, and the criminalization of poverty can intersect with lethal consequences for trans women of color.

On top of this, social service organizations like the Ali Forney Center the Marsha P. Johnston Institute are on the frontlines of providing crucial and life-saving services to vulnerable and at-risk LGBTQ youth and trans and queer people of color. But these are severely underfunded and lacking adequate resources to tackle the array of social problems at hand. As a result, these programs are often forced to rely on donations and support from within the community in order to survive. They face a bipartisan austerity regime that will make life even harder for those who need the most care.

Blood on their hands

Therefore, it is no exaggeration to say, in this context, that the Trump administration and the religious right have blood on their hands. These are not simply abstract policy debates but real attacks against LGBTQ people that jeopardize our victories. They attempt to re-legitimize a climate of homophobia and transphobia and will have damaging material impacts, especially on the lives of the most vulnerable queer and trans people.

The Trump regime is waging an offensive that calls for an all-out response. Instead, we have been left with a response from established LGBTQ organizations and a Democratic Party that has been passive at best and outright complicit at worst.

Mainstream LGBT groups have continued to place all of their faith, and millions of dollars, in the Democratic Party, pursuing a strategy of lobbying and campaigning for “pro-equality” candidates with little to show for it. This can be seen most recently in the Democratic Party establishment’s successful attempt to crush the insurgent campaign of Bernie Sanders, a longtime proponent of LGBTQ equality. They opted instead for the most underwhelming presidential candidate in modern American history: Joe Biden.

Although Democrats like to posture as “allies” of LGBTQ communities today, it was only a decade ago that the vast majority of Democratic politicians fully opposed gay marriage and refused to even utter the word “transgender.” Even now, the shift in rhetoric from mainstream Democrats has been the result of mass pressure and struggle from below.

Even worse, Democratic politicians, including self-identified “progressives” like New York City Mayor Bill DeBlasio, continually support austerity measures alongside increased spending on policing and incarceration, which disproportionally harms the most vulnerable.

The Birth of an Uprising and the Fight for Black Trans Lives

As it has done many times before, the Black liberation struggle is once again ripping open the Pandora’s box of American capitalism and exposing the brutal and twisted priorities of the modern world’s “greatest democracy,” so-called. George Floyd’s cry of “I can’t breathe!” was caught on camera as a white police office jammed his knee into Floyd’s neck, ultimately suffocating him. This has laid bare the hideous underbelly of America’s repressive apparatus, revealing the full extent of its racist raison d’être.

What the police murder of George Floyd has unleashed cannot be reduced to senseless violence and looting, as many in the corporate media and political establishment have tried to do. What began in Minneapolis has now spread to cities across the country and can only be described as a rebellion, spearheaded by Black workers and youth and on a scale and magnitude far wider and deeper than anything we saw in Ferguson or Baltimore.

This is a collective uprising, a national working-class rebellion, catalyzed by yet another police murder, but in response to something much deeper: a cataclysmic failure of the system to offer even the most basic standard of living or sense of dignity to the vast majority of working-class and poor people. This is a reality most acutely and disproportionately experienced by Black and Brown residents.

The coronavirus pandemic has only exacerbated the economic devastation in Black neighborhoods. Decades of government neglect and financial disinvestment, extreme poverty, depression levels of unemployment, and hypersegregation are all enforced by a militarized police state. This is the rotten soil that has birthed an unfolding rebellion, inspiring an entire country, and indeed, people around the globe..

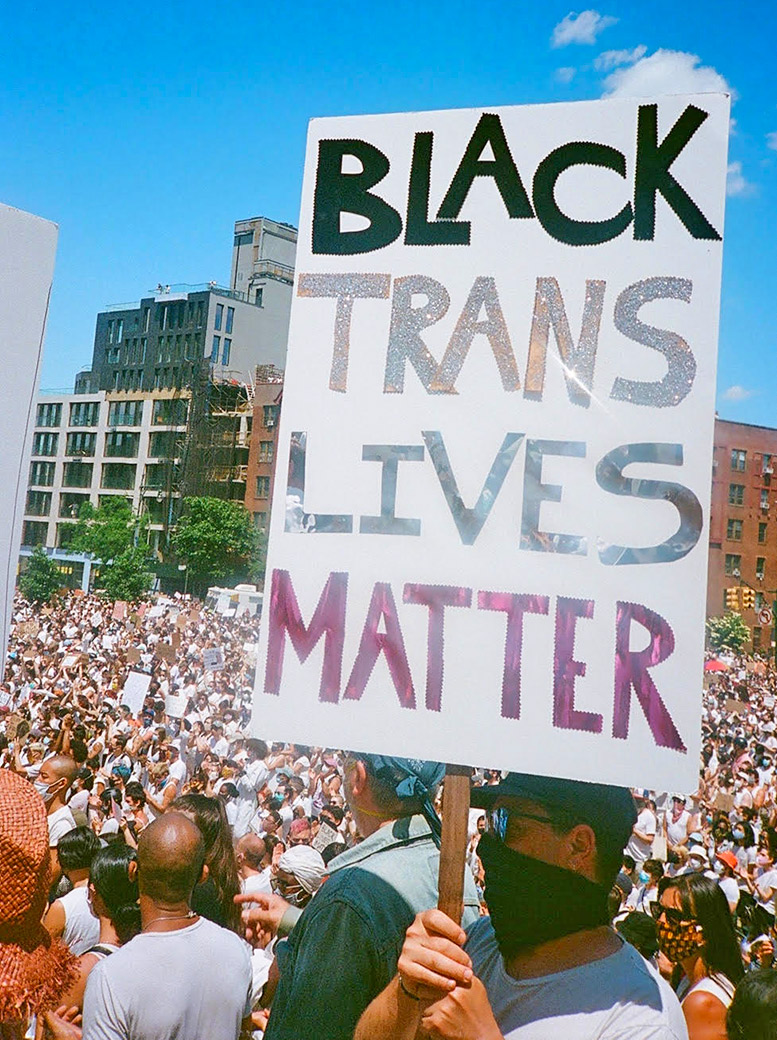

The Black Lives Matter rebellion has given rise to a historic breakthrough and development in the struggle for trans and queer liberation. On Sunday, June 14th, in Brooklyn, tens of thousands of people took over the streets to demand in unequivocal terms that Black Trans Lives Matter. Amidst a veritable sea of people with homemade signs, demonstrators highlighted the resiliency and power of Black trans activism and called attention to the range of issues effecting trans people of color. These range from housing discrimination and homelessness to disproportionate rates of violence, police brutality, and incarceration; and from barriers to accessing healthcare to the sidelining of trans people from the mainstream gay movement. The march was undoubtedly the largest single demonstration for trans rights, and Black trans lives in particular, in U.S. history.

It is clear that a profound shift is taking place: a rising generation of multi-racial, working-class trans and queer radicals are emerging, inspired by the militancy of Black Lives Matter and the resistance to Trump. They are fed up with and disconnected from the corporatization and white-washing of mainstream gay rights organizations, led by trans and queer people of color. They are demanding a new kind of queer movement.

This is (and must be) a movement foregrounding the connections between race, class, gender, and sexuality and rooted in uncompromising solidarity—a spirit of solidarity that goes beyond empty words and hollow gestures. This is solidarity grounded in actually standing and fighting alongside the most oppressed; rooted in centering the voices and experiences of those who have been historically marginalized, by a movement leadership that has been too enmeshed in the economic and political establishment to remain connected to the lived experiences of ordinary LGBTQ people.

This dynamic is not particularly new. In a previous era, the struggle of African-Americans against apartheid and Jim Crow gave rise to a generation of social movements and political dissent that transformed American society on a mass scale. They influenced everything from the antiwar movement in the wake of Vietnam to the Chicano and Women’s Liberation movement and eventually even LGBTQ struggles.

The Stonewall Rebellion

While LGBTQ political organizing certainly existed before Stonewall, most notably the 1966 Compton Cafeteria Riots in San Francisco, most of the work was underground, non-confrontational, and muzzled by McCarthyism. That started to change, however, as the Civil Rights Movement unfolded, and many young gay activists were inspired by Black activists who defied police terror and racist oppression.

Early gay rights organizations, such as New York’s Mattachine Society and the San Francisco-based Society for Individual Rights, began to take a more militant and unapologetic turn. Frank Kameny, an early gay activist, declared, “not only is homosexuality not immoral, but homosexual acts engaged in by consenting adults are moral, right, good, and desirable, both for individual participants and society.” Gay rights groups began organizing public demonstrations and “sip-ins” to demand the decriminalization of homosexuality and an end to anti-gay harassment at bars.

In May 1969 a young gay leftist in San Francisco named Carl Wittman penned “A Gay Manifesto,” an essay that would soon become a defining document in the gay liberation movement. Wittman’s words illustrate that the radicalization taking place among young, gay militants highlights the connections activists were beginning to make between homophobia, state repression, and police violence. His statement was a harbinger of things to come:

Straight cops patrol us, straight legislators govern us, straight employers keep us in line, [and] straight money exploits us. We have pretended that everything is OK, because we haven’t been able to see how to change it—we’ve been afraid. In the past year, there has been an awakening of gay liberation. How it began we don’t know; maybe we were inspired by black people and their freedom movement.

Where once there was frustration, alienation, and cynicism, there are new characteristics among us. And as we recall all the self-censorship and repression for so many years, a reservoir of tears pours out of our eyes. We are full of love for each other and are showing it; we are full of anger at what has been done to us. And we are euphoric, high, with the initial flourish of a movement.

The Stonewall Inn was one of New York City’s most popular gay bars in the 1960s. Sitting at the crossroads of Christopher Street and Seventh Avenue in Greenwich Village, a neighborhood known for its bohemian lifestyle, the Stonewall was dark and had two bars, a jukebox, and the only floor for dancing in the whole city. It became an epicenter for the gay world of New York, especially its most marginal members, and regularly drew an electric crowd of cruising gay men, drag queens, street kids, and lesbians.

At the beginning of the decade, laws across the U.S. were more repressive against homosexuals than any of the Soviet regimes the U.S. flagrantly criticized. A consenting adult who was caught having sex with another person of the same sex could face decades or even life in prison or could be confined to an insane asylum and subjected to electroshock therapy, castration, or lobotomy. Adults who were charged with a sex offense could lose their professional license and were often terminated from their jobs and barred from future employment.

Sex was not the only thing that could get you in trouble—clothes could, too, and that could be a problem for anyone brave enough to defy gender norms. Transgender people, cross-dressers, and drag and street queens were targeted and criminalized by the state. Wearing more than three items of clothing in New York City that did not correspond to one’s assigned gender was illegal and could result in arrest and imprisonment. Across the nation, gendered clothing laws that began to appear in the mid-19th century stayed on the books for decades, rendering variant gender expressions illegal.

While bars provided a place for gay people to meet one another and socialize in a repressive society, it also made them a target for police. Late on a Friday night in June 1969, police busted into the Stonewall, demanding that all patrons line up and show their IDs. The cops planned to arrest bar employees, cross-dressers, and those without proper identification.

That night the police were more aggressive than usual. They tore apart the bar, smashed the furniture, and were physically aggressive with patrons who talked back. Unlike previous raids that came early in the night, police shut the Stonewall during peak hours. Whereas normally patrons would disperse after being kicked out, knowing they could return later, this time they began to gather outside the bar. The crowd of a few dozen eventually swelled to hundreds. Thousands of gay residents poured into the streets.

The uprising was multiracial, diverse, and reflected a broad spectrum of the LGBTQ community. Many eyewitnesses commented specifically on the important role played that night by the most marginalized sections of the community — street kids, trans women, and queer youth of color.

But when the paddy wagons arrived, the mood changed drastically. Angry onlookers began throwing coins at police and then moved on to bottles, cobblestones, and trash cans. A full-fledged riot soon broke out.

Later that night the riot squad arrived, and a nightlong chase between gay and trans protesters and police ensued. Expecting to easily disperse a crowd of people that society had labeled “sissies” and “faggots” and stereotyped as weak, the police were caught completely off-guard when the protesters fought back. Pioneering transgender activist Sylvia Rivera was a part of Friday night’s uprising, which she would later describe as a turning point in her life. When a friend tried to convince her to leave, she said, “Are you nuts?! I’m not missing a minute of this—it’s the revolution!”

The Gay Liberation Movement

Stonewall marked a sharp break from the past and a qualitative turning point in the LGBTQ movement—not only because of the continuous rioting in the streets against police, but because activists were able to seize the moment and give an organized expression to the spontaneous uprising that encapsulated the militancy of the era. While the homophile movement made steady, if limited, progress throughout the 1950s and 60s and laid the basis for the gay liberation movement, Stonewall broke the dam of political and social isolation and catapulted the gay movement from the margins and into the open.

Activists did not waste a minute. Before the riots even finished, homophile militants created a flyer and distributed it to thousands of Village residents. It read, “Do you think homosexuals are revolting? You bet your sweet ass we are!” They described the Stonewall Rebellion as “the hairpin drop heard around the world.”

Michael Brown, a gay socialist involved in the New Left who helped pass out flyers at Stonewall, reached out to the Mattachine Society after the first night of rioting in the hopes of calling for an organizing meeting to tap into the new momentum. Brown’s proposal was not viewed warmly by everyone in Mattachine. Older activists were critical of the riots and did not want to disrupt the group’s relationship with the political establishment

Brown and other radicals put together a flyer with the heading “GAY POWER” that called for a “Homosexual Liberation Meeting.” They concluded by proclaiming, “No one is free until everyone is free!” The first meeting was held two weeks after the riots and drew forty people. It was here that activists first chose the name the Gay Liberation Front (GLF), modeled on the National Liberation Front, the communist guerrilla movement fighting against the United States in Vietnam.

In a statement for a radical newspaper called The Rat, the GLF defined their mission as follows:

We are a revolutionary homosexual group of men and women formed with the realization that complete sexual liberation for all people cannot come about unless existing social institutions are abolished. We reject society’s attempt to impose sexual roles and definitions of our nature…Babylon has forced us to commit ourselves to one thing … revolution.

When asked what made them revolutionaries, they replied: “We identify ourselves with all the oppressed: the Vietnamese struggle, the third world, the blacks, the workers…all those oppressed by this rotten, dirty, vile, fucked up capitalist conspiracy.”

GLF chapters quickly spread across the country, organizing dances to raise money and create spaces for gay people to meet one another outside of mafia-controlled bars. In the fall of 1969, the GLF created its own newspaper, Come Out!, which became a key means of disseminating ideas and movement information. Gay Power and Gay also premiered that year and each sold over 25,000 copies per issue.

The GLF organized protests and direct actions to pressure politicians to support gay rights and established community service programs to provide food and social services to LGBTQ street youth. GLF members took their political education seriously and sought to develop a Marxist analysis of gay oppression.

From the beginning, GLF members debated whether the group should focus exclusively on gay issues or connect itself with other struggles on the Left. This led to a split, with some activists leaving to establish a single-issue organization called the Gay Activists Alliance (GAA), which defined itself as a group “exclusively devoted to the liberation of homosexuals and avoids involvement in any program of action not obviously relevant to homosexuals.”

The GAA began to organize public protests, referred to as “zaps.” It disrupted meetings with the mayor and city council representatives in an attempt to pressure them to end job discrimination and police harassment against gays and lesbians.

This statement from Arthur Evans, a prominent member of GAA, sums up the group’s approach and contrasts sharply with the “don’t rock the boat” strategy pursued by established LGBTQ organizations today. Evans said,

We decided that people on the other side of the power structure were going to have the same thing happen to them. The wall that they had built protecting themselves from the personal consequences of their political decisions were going to be torn down … That meant in effect that we were going to disrupt Mayor Lindsey’s personal life … as a result of the political consequences of his administration.

The GLF and GAA collaborated on many projects, including the first annual march commemorating the Stonewall Rebellion, which took place in New York City and drew 10,000 people. The march quickly expanded to dozens of cities across the country and involved over 500,000 people.

One agenda item all gay liberationists shared was the emphasis on coming out publicly. Although coming out carried very real risks, it was also a cathartic experience that shed the shame and humiliation associated with living life in the closet and provided people with a newfound sense of pride and self-confidence.

As gay historian John D’Emilo points out, it also “provided gay liberationists with an army of permanent enlistees.” By coming out, the movement gained people who became personally invested in the future of the struggle and served as a pole of attraction to wider layers of people and new recruits. As gays and lesbians came out to friends, family, and coworkers, it made homosexuality seem more like a “normal” part of the social fabric and gave the movement new leverage in pushing for social change over the following decades.

Transphobia and the Gay Left

Like all movements, the fight for gay liberation contained political contradictions and internal problems. Even though transgender people played an important role in the riots and the movement that preceded it, their treatment in the movement was mixed, ranging from supportive to hostile.

Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson, active in both the GAA and GLF, became the movement’s most prominent trans activists. They formed a short-lived organization dedicated specifically to providing services to trans people and street youth called Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR). Although often rejected and only occasionally welcomed, they refused to leave.

As Rivera described it, she was never going to let anyone prevent her from fighting for her own cause. Even in the face of jeers and insults, she worked to convince her gay comrades of their shared interests with trans people and street youth who were brutalized by the same police and rejected by the same society as gays and lesbians. After Sylvia fought her way to the stage at New York’s 1972 Gay Pride march, she gave her famous speech “Y’all Better Quite Down Now!” which challenged the Gay Left’s transphobia. In this speech, she made an uncompromising case for the centrality of solidarity in the struggle for liberation:

Y’all better quiet down. I’ve been trying to get up here all day for your gay brothers and your gay sisters in jail.

You tell me to go and hide my tail between my legs. I will not put up with this shit. I have been beaten. I have had my nose broken. I have been thrown in jail. I have lost my job. I have lost my apartment for gay liberation and you all treat me this way? What the fuck’s wrong with you all? Think about that!

I believe in gay power. I believe in us getting our rights, or else I would not be out there fighting for our rights.

The people [STAR] are trying to do something for all of us, and not men and women that belong to a white middle-class white club. And that’s what you all belong to!

REVOLUTION NOW! Gimme a ‘G’! Gimme an ‘A’! Gimme a ‘Y’! Gimme a ‘P’! Gimme an ‘O’! Gimme a ‘W’! Gimme an ‘E! Gimme an ‘R’! Gay power! Louder! GAY POWER!

Although transgender people found support from a layer of principled gay liberationists and segments of the radical and revolutionary left, mainstream gay and lesbian organization abandoned the trans community. They consistently treated their demands for inclusion with out-right hostility, until at least the early 2000s.

As Susan Stryker demonstrates in “Transgender History: The Roots of Today’s Revolution,” despite the pivotal role played by trans and gender non-conforming people at Stonewall and in the early years of Gay Liberation, it would take over three decades of pressure to effect change. It was only after many years of organizing that mainstream gay and lesbian organizations would incorporate the transgender movement.

Even today, though much has changed, the struggle to foreground the experiences and demands of trans people within the broader movement for sexual and gender liberation is far from complete.

Lessons of Stonewall

So what should activists make of this history?

The first point is simple: rebellions work. Much like today’s anti-racist uprising, Stonewall marked a pivotal turning point in LGBTQ history. Change does not come because politicians introduce piecemeal legislation or because NGOs organize black-tie fundraisers. It happens when ordinary people take matters into their own hands–when they challenge institutions of state repression and become active participants in shaping their own world.

Stonewall and today’s unfolding rebellion demonstrates that there is power in numbers. What enabled the gay liberation movement to win significant reforms that had been unimaginable just a decade before was its mass character. Rather than settling for what the political establishment deems realistic, Black and Brown trans and queer people broke through the confines of their own oppression and demanded what was necessary to improve the material conditions of their lives.

As history continues to demonstrate, rebellions, because of their explosiveness, mass character, and militancy have the capacity to transform society’s political landscape and completely upend the parameters of what seems possible. Mass uprisings do more in a matter of days and weeks to advance the movement than years and decades of futile lobbying and electoral campaigns.

Second, police violence and incarceration are LGBTQ issues. Far from being an arbiter of justice, the criminal legal system functions to enforce hegemonic racialized and classed concepts of capitalist morality, sexual conformity, and compliance to traditional gender roles.

Ordinances criminalizing homosexuality and gender transgression, police raids on gay bars and cruising spots, the criminalization of LGBTQ homelessness and sex work in the era of mass incarceration: these are only a few examples of the state regulation of sexual morality and gender expression that are embedded within a system of policing and prisons designed to manage the symptoms of inequality. Moreover, they are designed to discipline the working class and oppressed communities and maintain a broader system of capitalist domination.

From the Compton Cafeteria Riots to the Stonewall Rebellion to the anti-racist uprising unfolding today, LGBTQ people—particularly people of color and working class and poor people—have always been at the forefront of struggles against racist police terror.

Third, solidarity is essential. What made the uprising at Stonewall so successful was the fact that it brought together a multi-racial, multi-gendered coalition of working-class and poor trans and queer people united against a common enemy. While race, gender, sexuality, and class played a role in shaping the way trans and queer people experienced life before Stonewall, it was a shared experience of oppression at the hands of a common enemy that provided them the basis on which to struggle together that night.

Gay Liberation’s insistence on the interconnectedness of liberation movements, its solidarity with the struggles of the most oppressed, and its willingness to challenge the capitalist social order made it both threatening and powerful.

However, as the radical movements of the 1960s and 70s began to go into decline in the face of increased state repression and cooptation by the Democratic Party and sections of capital, the political horizons and aspirations of the Left began to recede. The spirit of solidarity that had animated the militancy of the 1960s and 70s gave way to more conservative political formulations.

The gay and lesbian movement’s abandonment of transgender people is not only morally indefensible but represents a historic defeat for the movement as a whole. It is precisely this history of exclusion that makes today’s outpouring of transgender activism, led by young Black and Brown activists, such a historic turning point and advancement in the movement’s history. Imaria Jones, a Black transgender activist and writer, speaking recently on Democracy Now!, summarized the significance of the moment:

And I think that what’s really powerful about what happened on Saturday is that it was the culmination of a lot of knowledge in our community, the fact that even though Black and Brown trans women started the fight for LGBTQ liberation at Stonewall, that we were pushed out of it and have not benefited from the movement that we helped to start.

And we are saying that that’s not going to happen, that we understand from history that when we try to prioritize some rights over others, when we try to prioritize certain groups of people over others, historically, we know that all the rights that are gained that way are fragile, that they don’t last very long.

And so, the bottom line is that we all go, or nobody goes. And what we’re saying is that we’re going.

Fourth, organization matters. Spontaneity and organization are not mutually exclusive but are two aspects of the same process. Spontaneous uprisings like Stonewall and today’s anti-racist rebellion should be expected in a system in which people are beaten down and oppressed on a regular basis. Eventually, decades of passivity and conservatism crack and people are transformed as they are flung into a burst of activity. They begin to shed old ideas, changing themselves and the world around them in ways that had previously been unthinkable.

Outbursts are best understood not as ends in and of themselves, but as starting points in a process through which large numbers of people become politically conscious and begin to recognize their collective power. The trajectory of these struggles is not linear. Nothing in history is automatic. Movements face political questions about how to move forward, strategic debates emerge and organized political forces play a critical role in determining the direction of their struggle. Rebuilding open, democratic organizing spaces where ordinary people can begin to engage will be an important task for the movement today.

Lastly, formal rights, such as marriage equality and employment non-discrimination, are important and worth fighting for and defending. They provide tangible and concrete benefits that improve the lives of ordinary working-class trans and queer people and strike an ideological blow to the hegemony of reactionary ideas. It is this set of beliefs that props up and legitimates the oppression of trans and queer and sows further divisions within the working class.

However, such legal victories have their limits. Even in an era where LGBTQ people now have access to greater legal rights and formal equality than ever before, oppression for the vast majority of working-class and poor trans and queer people, especially those livings at the intersection of racial and class oppression, continues.

In order to address the crisis of working-class and poor trans and queer people, particularly people of color, the movement will need to go beyond formal equality under the law and take aim at the real, material conditions of trans and queer oppression. Our struggles will inevitability need to build solidarity with other movements of the working class and oppressed to challenge the priorities of a tiny, exploitative capitalist class that manage the resources and wealth of society at the expense of the many.

Defunding and dismantling a system of policing and prisons that criminalizes Black, Brown, and poor LGBTQ people is a crucial first step. These resources must be redistributed toward community needs and social programs, trans and queer inclusive single-payer healthcare (including HIV/AIDS and mental health services), safe and high-quality public housing, well-funded public schools that are affirming for LGBTQ youth, and a guaranteed living wage and universal basic income. These are just some of the measures that would radically transform the material conditions of life for the vast majority of trans and queer people, especially the most vulnerable and marginalized, and lead us further down the path toward an emancipated future.

As the renowned Black Marxist intellectual and prison abolitionist, Angela Davis recently explained in an interview, “We support the trans community precisely because the community has taught us how to challenge that which is totally accepted as normal. If it is possible to challenge the gender binary, then we can certainly effectively resist prisons and police.” I would add, that if we can undo the sexual and gender binary and imagine a world without the racist and violent apparatus of capitalist power and coercion, we must, by necessity, strive towards a socialist future grounded in human liberation and solidarity.

*Keegan O’Brien is a queer socialist activist and writer in Brooklyn, NY. He is a public school teacher and member of the Movement of Rank & File Educators and the Democratic Socialists of America.

[This article was originally published by SpectreJournal.]