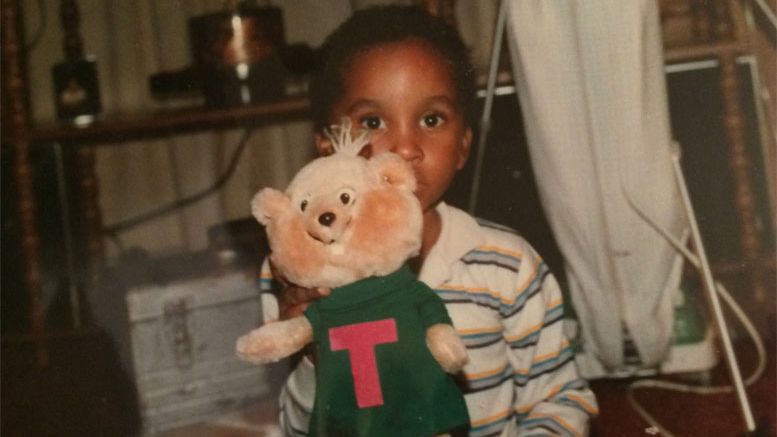

Michael Givens examines his past and how it shaped him into the man he is today.

By: Mike Givens*/Assistant Editor—

When I was 4 years old, my mother divorced my father. He was an abusive man who cared little for others and mostly for himself. It was the best decision she could have made for herself, my sister, and I.

My childhood was fraught with anxiety. I knew I was gay at an early age and, like many young gay boys, I repressed it. I was raised in a Southern Baptist family in southeast Virginia in a small town with small minds. I was a quiet young black boy whose imagination was his best asset, but who struggled deeply with the absence of his father.

I did well in school as I got older, played football for a small period of time in middle school and high school, and was generally liked by classmates, though the occasional “faggot” or “he’s weird” was lobbed my way. I was always soft-spoken and I remember constantly trying to make my voice lower, to not “sound gay.” Like many high schoolers, I did my best to fit in, but my quiet nature, preference for reading over sports, and my incredible social awkwardness (which persists to this day) always got the best of me.

And then college came, and so did the patterns. I’d find myself with intense crushes on straight classmates, men who had no interest in me other than friendship or casual acquaintanceship. It always felt like a piercing rejection to me, one that was intensely personal.

This behavior persisted throughout my 20s, through four years of undergraduate work, and continued when I moved to Boston for graduate school. Gay or straight, it was the men who were unattainable that were the most intoxicating, who seemed like the ones who I needed to be with. Every attempt at intimacy, at truly loving them, was met by rejection. I came on too strong. I professed feelings after only a few dates. I once told a man I’d been on two dates with that I loved him. I was the horror story you read about on Facebook or overhear at casual dinner parties with friends. Yes, I was “that guy,” the one you warned others about; the one who was too eager for a relationship.

Writing these words makes me cringe. Putting myself out there in such a deeply personal way makes me feel exposed, on display. But there’s power in naming something, in being able to see unhealthy behaviors, acknowledge them for what they are.

Quite frankly, in each of these failed pursuits I was replaying a very early rejection I experienced as a child: the abandonment of my father. I’ve heard the pseudo-psychological theories that gay men “choose” to be gay because of some deficit in their relationships with their fathers. My own mother told me that when I first came out to her when I was 23. I don’t buy into that argument at all. I think it’s an unfounded, desperate attempt to “explain” homosexuality in a way that is palatable to those who are unenlightened or need a definitive answer to explain away their prejudices.

However, what I will say is that our relationships with our parents play a very pivotal role in who we are. None of us escapes from childhood unscathed. Regardless of the quality of parenting we receive, we all have certain traumas we experience with our families, particular feelings; we carry with us into adulthood. And anyone who says otherwise is lying to themselves.

My father’s absence hurt me quite profoundly. It shook me to the core and never truly let go. I internalized my father’s rejection and generalized his abandonment. I let his absence, his rejection, make me feel inferior, unlovable.

And in adulthood I attempted to “fix” that in my romantic relationships. If I could find someone to validate me, make me feel special, loved, then it would somehow blot out the pain I felt. Hindsight being 20/20, those men I “fell” for, those relationships I pursued that ultimately failed, were part of a larger pattern, a cycle of trying to “get it right.” I had a childlike need for approval and affirmation that I projected onto romantic partners; a delusional belief that if someone could love me, see all of my flaws, then I’d have proof that I was worthy of loving myself.

But that’s not how life works. I could meet Prince Charming tomorrow, he could be everything I want in a partner, and it would not make up for my childhood. Likewise, I could reconcile with my father tomorrow and that also would not make up for his abandonment in my formative years. Loving someone doesn’t obliterate the scars of one’s past. Loving yourself, however, is like a balm, a soothing ointment that will not erase the scar, but will heal it. And at the end of the day we all need scars; they remind us of the past and encourage us to do better, to push forward and continue to love ourselves.

And thus my re-education begins. I let go. I accept the past for what it was. I acknowledge the fact that no human being can truly validate who I am and I dedicate each day to loving myself, valuing what I have to offer. Most importantly, I name the pattern, I own it, and I deconstruct it so that it no longer dictates how I live my life.

*A graduate of the Boston University College of Communication, Mike Givens has been a social justice advocate for more than eight years. During that time he’s worked on a range of initiatives aimed at uplifting marginalized populations. An experienced media strategist and public relations professional, Mike currently devotes his spare time to a number of vital issues including racial justice and socioeconomic equity.

I love you, Mikey!

-Your little sis

Genuine. Powerful. Empowering. A challenge to everyone to be their authentic self and grow. This raw honesty will inspire others spiritually and intellectually. Thank you for being vulnerable and at the same time strong and courageous.