By: Richard Labonte*/Special for TRT–

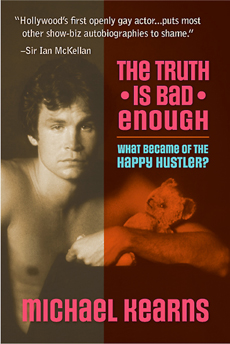

The Truth is Bad Enough: What Became of the Happy Hustler?, by Michael Kearns. CreateSpace, 294 pages, $15.95 paper.

First he was a precocious boy, acting in and directing plays – and reveling in sex with older men – before he finished high school. Then he was a serious actor, a serious drunk, a serial sexaholic, and, in the mid-1970s, a celebrated hoaxster, doing the talk show circuit as “Grant Tracy Saxon,” alleged author of a fake memoir, The Happy Hustler, all the while selling his body to eager johns (and appearing in a couple of episodes of The Waltons). Next came hard-won sobriety, AIDS activism, HIV infection, a series of searing one-man performances and of shimmering collaborations with his professional colleague, the late James Carroll Pickett. And now, still acting and directing (and surviving), Kearns is reveling in his finest role – father to an African-American child he adopted more than 15 years ago. Kearns is unsparing in recounting his addictive days, candid about how his queer and AIDS activism impacted his Hollywood career and – in the final chapters – luminous in imparting the love he shares with his daughter, who now aspires to be an actor, just like dad. This multi-textured memoir shimmers.

First he was a precocious boy, acting in and directing plays – and reveling in sex with older men – before he finished high school. Then he was a serious actor, a serious drunk, a serial sexaholic, and, in the mid-1970s, a celebrated hoaxster, doing the talk show circuit as “Grant Tracy Saxon,” alleged author of a fake memoir, The Happy Hustler, all the while selling his body to eager johns (and appearing in a couple of episodes of The Waltons). Next came hard-won sobriety, AIDS activism, HIV infection, a series of searing one-man performances and of shimmering collaborations with his professional colleague, the late James Carroll Pickett. And now, still acting and directing (and surviving), Kearns is reveling in his finest role – father to an African-American child he adopted more than 15 years ago. Kearns is unsparing in recounting his addictive days, candid about how his queer and AIDS activism impacted his Hollywood career and – in the final chapters – luminous in imparting the love he shares with his daughter, who now aspires to be an actor, just like dad. This multi-textured memoir shimmers.

Being Emily, by Rachel Gold. Bella Books, 210 pages, $15.95 paper.

Big hands, broad shoulders, solid biceps, hard chest, lanky swim team-honed body – teenager Christopher is all boy. But there’s a girl within, and her name is Emily. Around other lads, “Chris” slips into manly mode to avoid being the prey of high school bullies, but sets an alarm clock to 4 a.m. in order, behind a securely locked door, to don soft clothes and imagine a more feminine world. Chris’s goth girlfriend, Claire, is repelled when Chris tells her, heart racing, that “I’m a girl” – though she soon becomes a makeup-applying conspirator; Chris’s parents are both condescending and confrontational when they learn of Emily; even Chris’s first therapist insists that being an Emily is perverted. Salvation comes through a trans support group, a more supportive therapist and – a nice touch – fumbling but loving acknowledgement and semi-acceptance by Chris’s father. Gold’s young adult novel about the emotional and physical transition from boy to girl – despite repeated cloying, too-coy references to “boy parts”; what’s so awful about calling a penis a penis? – is a graceful novel about transitions.

Love, Christopher Street: Reflections of New York City, edited by Thomas Keith. Vantage Point Books, 406 pages, $18.95 paper

Back when Alyson Books was a going concern, then-editor Joseph Pittman published Love, Bourbon Street, celebrating New Orleans; Love, Castro Street, celebrating San Francisco; and Love, West Hollywood, celebrating Los Angeles. Missing? New York, of course. So, after a years-long hiatus, the queer-city series returns, at last, from a new press and to the city of Stonewall. Gay comic Bob Smith opens with a profoundly personal essay blending a brief history of LGBT comics, a memory-lane remembrance of early New York days, and a no-self-pity-here account of the progression of his Lou Gehrig’s disease (“I don’t even like baseball!”). Gay comic Eddie Sarfaty nicely bookends the collection with a closing essay about welcoming his sophisticated Manhattan friends to his mother’s very suburban home for an irreligious Passover feast. In between, mystery author Val McDermid recalls her first wide-eyed visit to Greenwich Village, publicist Michele Karlsberg reveals queer Staten Island, and more than 20 other writers (Thomas Glave’s is a most astoundingly literary reflection) tell how Manhattan and the boroughs shaped their queer lives.

Why is the Penis Shaped Like That? And Other Reflections on Being Human, by Jesse Bering. FSG/Scientific American, 288 pages, $16 paper.urbon Street, celebrating New Orleans; Love, Castro Street, celebrating San Francisco; and Love, West Hollywood, celebrating Los Angeles. Missing? New York, of course. So, after a years-long hiatus, the queer-city series returns, at last, from a new press and to the city of Stonewall. Gay comic Bob Smith opens with a profoundly personal essay blending a brief history of LGBT comics, a memory-lane remembrance of early New York days, and a no-self-pity-here account of the progression of his Lou Gehrig’s disease (“I don’t even like baseball!”). Gay comic Eddie Sarfaty nicely bookends the collection with a closing essay about welcoming his sophisticated Manhattan friends to his mother’s very suburban home for an irreligious Passover feast. In between, mystery author Val McDermid recalls her first wide-eyed visit to Greenwich Village, publicist Michele Karlsberg reveals queer Staten Island, and more than 20 other writers (Thomas Glave’s is a most astoundingly literary reflection) tell how Manhattan and the boroughs shaped their queer lives.

Most of the 30-plus columns here first appeared on ScientificAmerican.com; some are from the online magazine Slate. Research psychologist Bering writes about sex, life and the human condition – a handful of the pieces examine cannibalism, suicide, free will and religious belief – with such easy-going prose and ready wit that’s it not always apparent which outlet, the scientifically specialist or the lower-brow populist, spawned which essay. From the function of the scrotum to the purpose of pubic hair to the fact that humans masturbate far more frequently than other primates to assessments of assorted fetishes (podophilia, anyone?), Bering is often saucy and occasionally salacious but always factual – his prose is irresistibly irreverent, but he’s a writer who reveres scientific rigor. He’s also quite openly queer. Overall, his “reflections on being human” are unabashedly filtered through a personal, personable gay voice, and one section of the collection “The Gayer Science: There’s Something Queer Here,” addresses such LGBT issues as “homophobia as repressed desire” and “is your child pre-homosexual?”

*Richard Labonte has been reading, editing, selling, and writing about queer literature since the mid-’70s. He can be reached in care of this publication, or at BookMarks@qsyndicate.com.