New England Pride Guide 2018 | Special Edition

By: JP Delgado Galdamez/TRT Guest Columnist—

Almost two years ago, I was standing on the corner of Yonge and Dundas Street East in Toronto, Canada, for the city’s Pride Parade. My best friend invited me, and his partner drove about 10 hours to get us there. I was looking forward to having an amazing time as I remember being excited to see the international grand marshal, trans activist Aydian Dowling, and dance and cheer to the music. So, I waited. I waited and waited.

The parade was running late and I was upset. I was in full drag, in a sparkly oversized sweater—wrong outfit choice, considering it was a hot summer day—and hungry, the brunch we ate before the event was too small. It didn’t satisfy my hunger, but it sure ruined my lipstick.

After about 45 minutes, the parade arrived. I got to wave at Aydian! I danced and had a blast. When we got back to the hotel and I was able to access WiFi again I realized the reason why the parade was late.

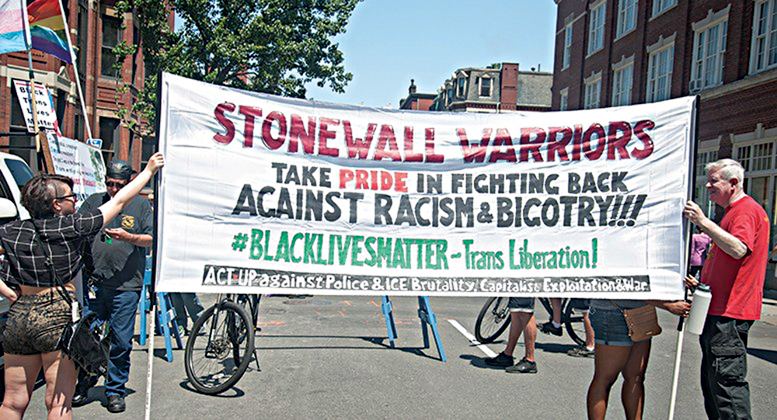

Black Lives Matter (BLM) Toronto stopped the parade with a sit-in that had a few different objectives. They wanted to hold Pride Toronto accountable for their anti-Blackness. They retook a space from which they had been excluded and erased.

Additionally, BLM Toronto had a list of demands, including changing Pride Toronto’s hiring policies to prioritize Black transgender women and Indigenous people. BLM Toronto also demanded that police floats no longer be allowed in the parade, to reinstate the South Asian stage, and to hold a public town hall between Pride Toronto and BLM Toronto within six months, which actually happened.

BLM Toronto also demanded more Black deaf and hearing sign language interpreters for the festival; BLM Toronto includes people with disabilities in their mission statement.

Pride Toronto signed the demands around 30 minutes after the parade had been stopped.

That same year, Boston Pride (BP) invited, then uninvited, Woburn Police Officer Anthony Imperioso to be one of the Pride marshals after public outrage over Imperioso’s, “inappropriate, offensive, and bigoted statements about Black Lives Matters protestors, Muslims, and people on welfare” on Facebook. Those comments are no longer public [but some can be accessed here.

The year prior, 2015, Massachusetts communities and organizations implemented an action at the Boston Pride Parade, using the campaign #WickedPissed, a direct clap-back at BP’s theme “Wicked Proud.” The list of demands, some directed to BP and others to the Boston LGBTQ community, did not include any mention about accessibility services and the inclusion of LGBTQ disabled folks.

In the meantime, Boston, and their communities and organizations within, still struggle with its racism and accessibility.

Accessibility Isn’t Limited to Physical Barriers

A study by the Ruderman Family Foundation, an organization advocating for the inclusion of people with disabilities throughout our society, states that up to half of the people killed by police have a disability. People with disabilities face disproportionate violence from police, similarly to people of color, transgender people, queer people, and immigrants.

That is why BLM Toronto’s action was so important. BLM Toronto focused on integrating many other identities that can intersect with Blackness and formulated demands that address different types of needs, some of which are specific to certain communities, others that are so broad that the entire LGBTQ community benefits from them.

By asking Pride Toronto to not allow police to march in the parade, BLM Toronto helped Pride Toronto to further center people with disabilities, as well as queer and trans folks, Black folks, and all other people of color, survivors of abuse, and others.; instead of providing a platform to violent and oppressive systems like police.

Ableism and racism aren’t the only issues within law enforcement. Domestic violence is two to four times more common among families with a police officer than American families in general. A police department that has domestic violence offenders among its ranks will not effectively serve and protect victims in the community, including people with disabilities who are survivors of domestic violence.

BLM Toronto’s demands for Pride Toronto were concise: they demanded police floats not be allowed in the parade, implicitly acknowledging that police presence is required for an event of such size. BP’s parade is the largest in New England, and according to BP’s marshal orientation, the fourth largest parade in the country. Police presence at the event is expected.

Historically, Pride, nonetheless, was a riot against police. A riot which was led by transgender women of color, many who happened to also have a disability. By asking the police to not participate in marching in the parade, Pride Toronto sent a message of commitment to continue working towards justice for all LGBTQ people.

LGBTQ police officers are, obviously, welcome to march in the parade, just as long as they’re not wearing the uniform that has, for many of them, protected from consequences after unnecessarily and unfairly killing Black, brown, queer, trans, women and/or people with disabilities.

Making spaces safer for people with disabilities means rejecting individuals and organizations that are violent against the disability community and/or people with disabilities. Any barrier that may prevent a person with a disability from going to an event, even if there are no physical barriers, is an accessibility issue.

Accessibility Facts about BP’s 2018 Parade

As of today, police are still allowed to march in the BP parade.

This year, BP is taken steps to provide more accessibility to the disability community. They partnered with Old Town Trolley Tours to provide a “handicap-accessible trolley” for elderly folks and those with disabilities who wish to be part of the parade. BP is also implementing a “handicap-accessible viewing area” for folks who wish to watch the parade from a safer, dedicated platform. To access these services, please contact parade@bostonpride.org.

BP’s concert will also be wheelchair-accessible and have American Sign Language interpretation.

[Read this story in Spanish here.]

*Born and raised in El Salvador, JP Delgado Galdamez is a Boston-based activist, drag performer, and educator. They focus on bringing together politics, anti-oppression work, and comedy through lip-synching and commentary. When JP isn’t performing, they are doing training and outreach for The Network/La Red, a local LGBQ/T social justice organization that works towards ending partner abuse. You can follow them at @dragqueenjp on social media.